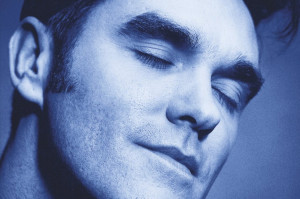

Back in the ’80s when The Smiths were a going concern I was going through my heavy metal phase, and they completely passed me by, dismissed as “something for the cool kids” (one of which I most certainly was not). Many years later, in college (and quite possibly thanks to the girl I was dating) I finally ‘got’ The Smiths, and set about devouring their back catalog with a vengeance. I also picked up a fair bit of Morrissey’s solo output, although that has proven to be much patchier. Still, even with some occasional lapses in the music quality control department, Morrissey’s lyrics have (generally) entertained, and his more-or-less steady appearance in the press (albeit usually through his court battles, militant vegetarianism, and general ability to wind people up, rather than for his music) has continued to provide some memorable quotes. So I was delighted when he released what I hope is simply Volume 1 of his memoirs – the literally-titled (pun intended) Autobiography – late last year. I ordered my copy from England the day it was released, and was mightily glad that I did so, as I think I finished it before it even made an appearance on the shelves in the U.S., such was its irresistability. (Sadly, it’s taken me a little longer to pen this ‘review’.)

Morrissey, being the determined individualist he is, has crafted a singular book with its own style, and its own literary conventions. There are no chapters, the entire book being a single, 450+-page screed, and we’re some six pages in before he even breaks for a second paragraph. Surprisingly, it works, making the book something that you just want to keep reading, without pause. It’s largely chronological, but this can be misleading, as sometimes one paragraph gives way to another that is set a few years later, yet in some places a dozen pages can pass without advancing time at all, and then in other places, a brief reminiscence can push you back a dozen years. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say that the first two thirds of the book (and certainly the first third) are based on diaries kept at the time, as the feelings of these times are captured far too well to be the product of a bout of reminiscing in front of a typewriter (or dictaphone – although it most certainly is not ghost-written, I’m not sure if Morrissey had the patience to type it all up himself…), and the latter third the product of memory. This is in some regards unfortunate, as it gives the feeling of a rush (and a push) towards the end, but in truth, it is perhaps the formative years of the young Mr. Morrissey that prove the more interesting anyway.

Morrissey, being the determined individualist he is, has crafted a singular book with its own style, and its own literary conventions. There are no chapters, the entire book being a single, 450+-page screed, and we’re some six pages in before he even breaks for a second paragraph. Surprisingly, it works, making the book something that you just want to keep reading, without pause. It’s largely chronological, but this can be misleading, as sometimes one paragraph gives way to another that is set a few years later, yet in some places a dozen pages can pass without advancing time at all, and then in other places, a brief reminiscence can push you back a dozen years. If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say that the first two thirds of the book (and certainly the first third) are based on diaries kept at the time, as the feelings of these times are captured far too well to be the product of a bout of reminiscing in front of a typewriter (or dictaphone – although it most certainly is not ghost-written, I’m not sure if Morrissey had the patience to type it all up himself…), and the latter third the product of memory. This is in some regards unfortunate, as it gives the feeling of a rush (and a push) towards the end, but in truth, it is perhaps the formative years of the young Mr. Morrissey that prove the more interesting anyway.

Readers hoping for a book about The Smiths will probably be sorely disappointed, though. It’s a full 144 pages before Morrissey even meets Johnny Marr, and then 80 pages later The Smiths have unfortunately split and we’re only halfway through the book. This is probably justified, as The Smiths only really lasted four years (’83 – ’87), whereas the solo Morrissey has been releasing albums under his own name since then, clocking up nine studio albums to The Smith’s four. That said, anyone wanting to understand the drive behind The Smiths’ songs will certainly enjoy the revelations about his early experiences and his (sometimes confounding) influences. Suddenly, so much of Morrissey’s output makes (more) sense.

That’s not to say that you necessarily have to be a die-hard Smiths – or Morrissey – fan to enjoy the book. As one would expect from someone who has built himself a career on words, it’s a thoroughly enjoyable read. There’s some genuinely (and deliberately) funny moments in the book, and Morrissey’s colorful prose had me laughing out loud on more than one occasion, such as this description of one Manchester club:

“The Electric Circus is surrounded by condemned yet fully inhabited 1930s council traps from where mutant dwellers of the most hunchbacked and club-footed type swarm out in order to make fun of the pop kids who line up outside the Electric Circus. Manchester’s most pickled poor live in these surrounds – non-human sewer rats with missing eyes; the loudly insane with indecipherable speech patterns; the mad poor of Manchester’s armpit. Dickens himself would be lost for words.”

Although Morrissey does not necessarily endear himself to people with such descriptions as this (and the no-less-offensive “Stuffed coaches from Blackburn and Bolton would pull up outside [the Hacienda Club], unloading disfigured disco dancers and goblinesque pork-pie chubbos with carroty-red curls smelling of pickled pig”), on the whole he does actually come across as a very sympathetic character. It’s difficult not to be moved by his early acceptance of his feelings of alienation and not belonging, and to not want to just give him a hug when circumstances conspire against him, leaving him lost and bewildered. He appears to have always been aware of his social shortcomings from an early age, but seems to be entirely unable to do anything about it, sometimes appearing to be nothing more than a sympathetic bystander to his own life. So given this background, you can forgive him the occasional self-aggrandizement in the latter sections of the book, when his record sales and concert sizes significantly exceeded those of The Smiths, and he takes great delight in pointing this out, and in describing the love and adoration of his increasing army of fans.

That he managed to scale to such heights at all is a miracle in itself as, by account of this book, Morrissey seems to have been the most unlucky person ever to stumble into ‘showbusiness’, given the degree to which he has apparently been mis-managed, mis-represented, and mis-treated. Nowhere in the book is this laid more bare than in the High Court case from 1996 in which Mike Joyce (he was the drummer in The Smiths – it speaks volumes that I need to explain this!) ludicrously claimed rights to 25% of The Smith’s royalties. Given that from the beginning of the Smiths, credit for The Smiths’ songs was listed as “Lyrics: Morrissey, Music: Marr”, and publishing was by “Morrissey/Marr Music”, it’s difficult to see how Joyce could in all honesty claim such a thing. I don’t think he’s done anything since The Smiths disbanded, and were it not for this court case, people probably wouldn’t even know his name today. Yet through the incompetence of Morrissey’s solicitor, and the willful mis-rulings of a septuagenarian judge who had never heard of The Smiths and had little knowledge of the machinations of the music industry, Morrissey (and Marr) actually lost. True, the book shows only Morrissey’s side of things, but it’s a very compelling side nonetheless. Ironically, Morrissey is very complimentary about the musicianship of Joyce (and Rourke) – probably more than Joyce deserves – but Morrissey certainly tears into him, with no holds barred, over the court case. It’s a pity that Morrissey devotes a reasonable slice of the book to airing grievances (which does little to further the narrative or expand the insight), but he’s hardly the first person to do so in an autobiography.

Such is the polarizing nature of Morrissey that it is difficult to see there being much of an audience for this book beyond his current compliment of fans, which is unfortunate, because it really is an enjoyable read. Haters gonna hate, and if you don’t like Morrissey this book probably isn’t going to change your opinion of him, but if you want to appreciate the context of Morrissey’s work a little better, and be entertained in the process, you should read this book. Just make sure you have a stack of The Smiths and Morrissey albums to hand so that you can cue up the music he mentions, as you read about it. Or is it just me that does that?

Leave a Reply